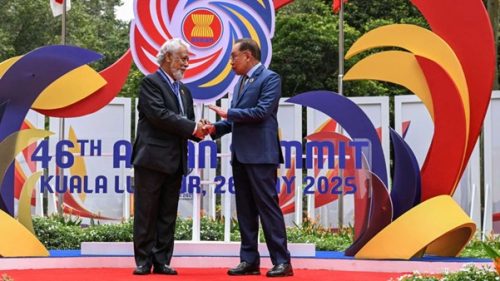

Image: AP via World Politics Review

At the end of this month, Timor-Leste will officially join the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as its eleventh full member. The decision to admit Timor-Leste to the regional bloc represents both a major diplomatic milestone and the beginning of a new phase in its regional integration. Timor-Leste’s entry into ASEAN has also drawn regional and international attention because it occupies a distinctive place in the geopolitical landscape of Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Its strategic importance does not derive primarily from natural resources, population size or market power, but from two other factors – its location and its political history.

Geographically, Timor-Leste lies at the intersection of Southeast Asia and Oceania, and between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The Ombai-Wetar Strait, which passes along the country’s northern coast, is one of only two deep-water channels linking the Pacific and Indian Oceans that can accommodate fully submerged nuclear submarines. This makes Timor-Leste part of a vital maritime corridor in global naval strategy, especially for maritime powers such as the United States, China and Australia that compete for influence in the Indo-Pacific.

Politically, Timor-Leste represents one of the world’s most prominent examples of international state-building. Since 1999, this country has been the focus of large-scale UN and donor programs aimed at building democratic institutions, human rights protections and rule of law. For many international partners, Timor-Leste continues to be held up as a “success story” – a small country that achieved independence through struggle, and then achieved sustained peace through democratic institution-building, supported by significant outside assistance.

These geographical and political characteristics place Timor-Leste at a crossroads between Asia and the “political west”, and between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They also explain why Timor-Leste is becoming a site of geopolitical and geoeconomic contestation.

Geopolitics and Geoeconomics in Timor-Leste

In simple terms, geopolitics refers to the ways that geography, power and security interests shape relations between states. Geoeconomics refers to how countries use economic tools such as trade, investment and finance to achieve political or strategic goals.

Since independence, Timor-Leste has become a site of significant – and growing – geopolitical and geoeconomic contestation. Liberal democratic partners, including Australia, New Zealand, the United States, the European Union, South Korea and Japan, have invested heavily in security cooperation, state institutions, elections and human rights programs. At the same time, the non-liberal, socialist, party-state People’s Republic of China has expanded its presence through infrastructure projects, goods trade, gifted government buildings and proposed investments in fisheries and tourism. The differences in these forms of cooperation reflect, in part, competing visions of how Timor-Leste could develop institutionally and economically, as well as the strategic interests of external partners.

For Timor-Leste, balancing these external relationships to avoid dependency on a single set of partners has long been a central pillar of its foreign policy. Joining ASEAN now adds another layer to that balancing act, offering new opportunities but also exposing the country to fresh geopolitical and economic pressures.

ASEAN Accession: Strategic Benefits and Trade-Offs

Some observers believe that by becoming a member of ASEAN, Timor-Leste will gain protection against the risks of great power competition, as ASEAN plays an important role balancing regional interests through multilateral engagement, security cooperation and economic integration.

Australia may also support Timor-Leste’s entry into ASEAN as this provides a means to reduce Australia’s perceived “security burden” in Timor-Leste. Australian concerns about Timor-Leste’s fragile institutions and ability to navigate regional geopolitical competition have been major factors driving its extensive security cooperation with Timor-Leste in relation to military, policing and intelligence. From Canberra’s perspective, Timor-Leste’s accession to ASEAN could mean that its internal stability becomes partly an ASEAN concern, while ASEAN’s collective interest in maintaining regional balance could help limit Chinese influence.

For their part, some elites in Timor-Leste may view ASEAN accession as a way to reduce security dependency on Australia, a country which is viewed with some degree of distrust due to historical issues related to its diplomatic support for Indonesia’s military occupation and post-independence oil politics, particularly the fraught negotiations and espionage related to Greater Sunrise.

For Timor-Leste, ASEAN membership carries additional advantages. While individual member states may “lean” toward one side or another in global power rivalries, ASEAN operates as an important geopolitical entity in its own right. Within an emerging multipolar international order, ASEAN can be seen as one of several regional poles with its own norms and institutions. Membership therefore grants Timor-Leste a degree of autonomy and legitimacy within a broader, more cohesive regional framework. While some ASEAN-based analysts have expressed concern about how Timor-Leste’s close relationship with China will impact ASEAN internally, they remain optimistic that these impacts will remain manageable by the bloc.

At the same time, integration into ASEAN also means Timor-Leste must adapt itself more to the region’s complex political and economic realities. Timor-Leste will need to align its policies with ASEAN’s consensus-based decision-making, which can limit space for independent diplomacy on certain issues. This will likely have significant implications for its outspoken advocacy on regional issues such as democratic transition in Myanmar.

Timorese Political Culture and Identity within ASEAN

The geopolitical implications of ASEAN membership cannot be understood without examining how Timor-Leste’s political system is perceived externally. Since independence, the country has been frequently described as “the most democratic country in Asia,” a narrative repeated by diplomats, donor agencies and international media. While this view tends to refer to Timor-Leste’s constitutional protections of freedom of speech and assembly, it is also shaped by Timor-Leste’s origin as a UN-led state-building project and extensive cooperation with liberal democratic states. Within this framing, Timor-Leste is viewed as part of the global community of democracies – a moral success story that stands apart from the region’s more “authoritarian” or illiberal regimes. For Timorese leaders, Western partners and development agencies alike, this narrative has practical value: it legitimises the post-independence state-building process, sustains donor confidence and elevates Timor-Leste’s standing in international fora.

While there is truth to the image of Timor-Leste as a highly “democratic” state, it does not fully reflect the complexities of the local political landscape. As FM has often argued, Timor-Leste’s political culture and governance differ significantly from the liberal democratic model that its institutions follow on paper. Power and decision making in Timor-Leste remain deeply rooted in patriarchal, hierarchical and personality-based traditions that predate independence. Political authority is heavily mediated through traditional hierarchies, kinship networks and relationships forged during the resistance struggle. The institutions created under UN supervision were layered onto these indigenous systems and realities, resulting in a hybrid political order which outwardly resembles a Western-style liberal democracy, but in reality operates according to informal norms of seniority, personal prestige and patronage. Decision-making across government and society is still profoundly shaped by these indigenous structures and practices, which often contradicts Western notions of transparency, separation of powers and impersonal governance.

This tension between image and reality also shapes Timor-Leste’s international relations. The country is praised by liberal partners as a democratic success story, yet domestic mistrust of Australia remains strong due to past disputes. At the same time, Timorese leaders maintain close and pragmatic ties with China, whose state-led development model and non-interference approach align more comfortably with local political traditions. ASEAN membership could alter these dynamics by broadening Timor-Leste’s diplomatic space and reducing its dependence on recognition by liberal democracies for legitimacy.

Within ASEAN, the “ASEAN Way” and the associated debates about “Asian values” offer a contrasting framework to Western liberal democracy. These principles emphasise community harmony, respect for hierarchy and pragmatic cooperation, rather than Western-style adversarial politics and emphasis on individual rights and freedoms. The debate around “multipolarity” is also highly relevant: this concept has been advanced by countries such as China as an alternative framework which enables non-western, non-liberal states to articulate and legitimate their own distinctive political forms and economic development models in a world no longer unilaterally dominated by the United States. Indeed, the idea that a new, multipolar world order is emerging is increasingly acknowledged by diverse actors including the Munich Security Conference and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. For Timor-Leste, this shifting geopolitical environment may provide space to articulate its own form of democracy that reflects its historical, social and cultural realities – a social democracy with Timorese characteristics.

In this sense, ASEAN membership could serve not only strategic or economic purposes, but it may also allow Timor-Leste to move beyond its externally imposed identity as a UN liberal state-building project, and instead embrace a more locally grounded national political identity. Among ASEAN’s mix of political systems, Timor-Leste could position itself as a bridge between liberal and non-liberal worlds – a country that upholds democratic ideals and individual human rights while grounding them in indigenous traditions and social structures.

Geoeconomic Opportunities and Risks

While economic integration with ASEAN could bring major benefits through trade, investment, infrastructure and tourism, it also carries significant risks. One of the most pressing is the connection between economic integration, weak regulation and transnational organised crime. Increased trade and movement of goods, capital and people can also create opportunities for illicit economic activities, particularly when regulatory and policing capacity is limited. Southeast Asia already serves as a global centre for organised crime, including drug trafficking, human trafficking, wildlife trade, money laundering and illegal online operations. Timor-Leste’s integration into this regional economy therefore brings not only opportunities but also serious challenges related to criminal activity.

The recent scandal surrounding foreign investments in offshore gambling illustrates this point clearly. The government’s decision to cancel the iGaming licence followed widespread concern about criminal infiltration and the damage to Timor-Leste’s international reputation, as well as a police raid on a suspected cyber-fraud centre in Oecussi. Despite the cancellation, questions remain about who authorised the investment and whether it was linked to broader organised criminal networks in the region. Moreover, without significant investment in capabilities to combat sophisticated cyber and financial crimes, Timor-Leste remains vulnerable to further infiltration by criminal networks operating across Southeast Asia.

Geopolitical implications of “Chinese organised crime”

Much of the geopolitical debate regarding Timor-Leste focuses on China’s influence. Chinese presence has grown through construction projects, trade and bilateral engagement. Historically, Chinese traders and later Hakka settlers from Macau played a major role in Timor-Leste’s economy long before independence. Today, Chinese businesses dominate much of the private sector, from retail and construction to hospitality.

One reason for the outsized economic role of Chinese actors in Timor-Leste lies in the structure of international cooperation since independence. UN and Western donors focused heavily on building institutions, human resources and democratic governance, but much less on physical infrastructure and trade. China filled that gap, offering visible projects and direct investment where other partners did not.

While most Chinese business activities are legitimate, the sheer volume of trade and investment – along with Timor-Leste’s weak regulatory capacity and personalised system of governance – have made the growth of China-linked organised crime almost inevitable. Moreover, Timor-Leste’s history of clandestine resistance has resulted in entrenched power networks skilled in secrecy, logistics and informal exchange, attributes which lend themselves well to corrupt dealings and organised crime.

Recent reports of criminal enterprises involving Chinese nationals have led to government action and international reporting. It may be that ASEAN partners or other regional actors expressed concern that such activities could undermine Timor-Leste’s standing as a prospective member. ASEAN places significant emphasis on regional stability and reputation, and its members are wary of criminal economies that could spill across borders. The timing of the government’s decision to cancel the iGaming licence and take action against cyber-fraud centres. The official resolution cancelling the iGaming licence cited concern over the country’s “international reputation” – a phrase suggesting that external diplomatic considerations played a role.

The convergence of politics, business and crime threatens not only public trust and wellbeing but also the country’s international reputation as a democratic and law-abiding state. As FM has written, it is essential that Timor-Leste enhance its capacity to detect and prevent the infiltration of this country by transnational criminal actors, which includes not only enhancing policing capacity, but taking serious action against public officials who collude with criminals. In addition, weak institutions not only create internal risks but also limit the country’s credibility in regional forums. For Timor-Leste to benefit fully from ASEAN membership, strengthening transparency and enforcement capacities will be essential.

Balancing External Relationships: A Multi-Vector Foreign Policy

Even as a member of ASEAN, Timor-Leste will continue to pursue a multi-vector foreign policy aimed at maintaining balanced relations with a diverse set of partners. Engagement with ASEAN does not replace long-standing cooperation with Australia, New Zealand, Portugal, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and South Korea. These relationships remain crucial for human resource development, education, institutional strengthening, policing, defence and sustainable economic growth.

ASEAN membership also aligns with Timor-Leste’s consistent advocacy for multilateralism, international law and peaceful conflict resolution. Within ASEAN, Timor-Leste can act as a constructive voice for dialogue, human rights and non-alignment, reflecting the Timorese people’s unique historical experience and moral credibility. However, ASEAN’s internal diversity means that positions on major global issues often vary widely among its members. Timor-Leste will need to navigate these differences carefully while maintaining its commitment to democratic principles and regional harmony.

Conclusion

Timor-Leste’s accession to ASEAN marks a major step in its long-term integration into the regional political and economic order, and a significant diplomatic triumph. The move reflects both pragmatic and symbolic considerations: the pursuit of stability, markets and investment, but also the consolidation of a national identity rooted in peacebuilding, social democracy and regional connections.

At the same time, ASEAN membership will expose Timor-Leste to complex geopolitical and geoeconomic pressures. To ensure that ASEAN integration strengthens rather than weakens national sovereignty, Timor-Leste must continue building transparent governance, resilient institutions and effective law enforcement. Managing relations with competing external powers, strengthening policing and intelligence capacity, including through continued external cooperation, and maintaining independent decision-making will be key to preserving national stability and international credibility. At the same time, by asserting a distinct national political identity, shaped by global norms but rooted in indigenous structures and beliefs, Timor-Leste can forge a truly independent path and consolidate its own form of social democracy.